Romeo and Juliet may not be as quotable as Hamlet, but we still have "parting is such sweet sorrow", "fool’s paradise" and the thunderous "a plague on both your houses!"

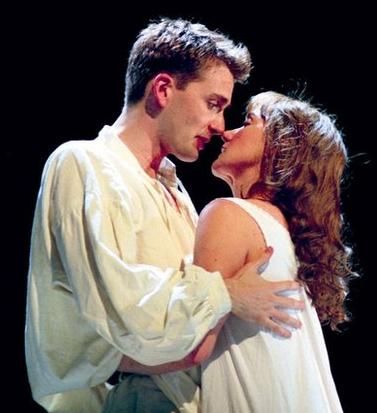

In the Shakespeare on 3 production, the last of these was voiced by Paul Ready, playing Mercutio. David Tennant was Prince Escalus, with Trystan Gravelle and Vanessa Kirby playing our star-cross’d lovers (right).

Juliet had "not seen the change of fourteen years" – she was 13. According to historian Tim Lambert, rich families had their daughters marry young – in the 16th century, at the end of which the play was written, marriage was legal from the age of 12, although this might be honoured in the breech ("younger than she are happy mothers made" says Juliet’s admirer Paris to her father). Capulet suggests another two years "ere we may think her ripe to be a bride": was Shakespeare condemning child marriage?

It wasn’t until 1763 that an amendment to Lord Hardwicke’s Marriage act of 1754 raised the marriageable age to 16, but consent to sex wasn’t raised to 13 until 1875, thence to 16 in 1885 after WT Stead’s crusading campaign against child prostitution. Child protection has been a long time coming, and heaven knows what miseries young girls suffered because few cared.

So why were men allowed to force 9-year-old girls to marry them in contemporary London with the knowledge and therefore implicit co-operation of their teachers?

Since the girls are not from a European tradition but are Muslims, it seems they live in a bubble free of womens’ rights with the blessing of those who demand these rights everywhere else.

Until all children in Britain enjoy child protection as prescribed by British laws, Romeo and Juliet's other tragedy - young girls denied their childhood - will play out in real life again and again.

Gerry Dorrian

300 words

Click to go to BBC Radio 3's Shakespeare on 3 homepage

Click for the script of Romeo and Juliet

Go to journalist Jon Slattery's blog to read why WT Stead's work is still relevant today