The Channel 4 documentary Prejudiced and Proud might easily have been depressing viewing: the English Defence League was referred to yet again as a "far-right" group, despite its eschewal of David Cameron’s “multiculturalism has failed” narrative putting its members to the left of over half of the MPs in Westminster. The narrator referred to founder/leader Tommy Robinson’s "misguided beliefs" with no corresponding disapprobation of fellow Lutonian Sayful Islam’s doctrines; and Islamist protesters’ faces were pixillated out, a courtesy not extended to EDL members. In short, the documentary observed the shibboleths of "liberal" media values which must have giants of political liberalism like Locke and Jefferson turning in their graves.

The Channel 4 documentary Prejudiced and Proud might easily have been depressing viewing: the English Defence League was referred to yet again as a "far-right" group, despite its eschewal of David Cameron’s “multiculturalism has failed” narrative putting its members to the left of over half of the MPs in Westminster. The narrator referred to founder/leader Tommy Robinson’s "misguided beliefs" with no corresponding disapprobation of fellow Lutonian Sayful Islam’s doctrines; and Islamist protesters’ faces were pixillated out, a courtesy not extended to EDL members. In short, the documentary observed the shibboleths of "liberal" media values which must have giants of political liberalism like Locke and Jefferson turning in their graves. And yet, members of the EDL and its friends in the British Freedom Party were celebrating, some literally, at the unprecedented coverage of the EDL’s aims and methods, the League’s website nearly crashed through the volume of traffic and during the programme Tommy’s name trended internationally on Twitter.

And yet, members of the EDL and its friends in the British Freedom Party were celebrating, some literally, at the unprecedented coverage of the EDL’s aims and methods, the League’s website nearly crashed through the volume of traffic and during the programme Tommy’s name trended internationally on Twitter.It’s a programme the BBC simply couldn’t have commissioned. For one thing, not having attended public school or gained a degree, Tommy’s not somebody whom BBC bosses would call "one of us". For another, the Establishment worship of beard-and-burqa extremism is so entrenched that Jeremy Paxman, in his infamous Newsnight interrogation of Tommy, refused to accept that there was any more of a problem with Pakistani paedophiles than with those of any other ethnicity.

Tommy’s closing comments were invaluable, and it was brave of Channel 4 to broadcast them: "People are angry, and they need some way to express their anger...Take that away, and you’ll start to see things get blown up." I hope those politicians who were happy to let the IRA bomb its way to the negotiating table, and to watch Basque and Palestinian terorrists do the same, engrave those words on their hearts.

Tommy’s closing comments were invaluable, and it was brave of Channel 4 to broadcast them: "People are angry, and they need some way to express their anger...Take that away, and you’ll start to see things get blown up." I hope those politicians who were happy to let the IRA bomb its way to the negotiating table, and to watch Basque and Palestinian terorrists do the same, engrave those words on their hearts. Click to find out more about Proud and Prejudiced and watch the documentary

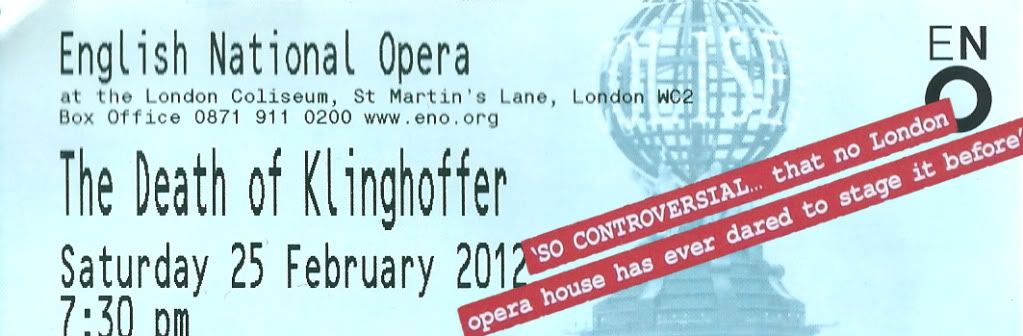

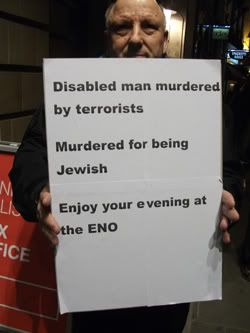

It was a restrained protest, very British: the single protester (who gave me permission to photograph him) carried a placard reminding patrons of the

It was a restrained protest, very British: the single protester (who gave me permission to photograph him) carried a placard reminding patrons of the

Towards the end of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, Tony Benn referred to those who had "left their faces in the Falklands", and finally apologised on Question Time when Robin Day (right) – also nearing the end of his tenure – told him of the offence his remark had caused nationally.

Towards the end of Margaret Thatcher’s premiership, Tony Benn referred to those who had "left their faces in the Falklands", and finally apologised on Question Time when Robin Day (right) – also nearing the end of his tenure – told him of the offence his remark had caused nationally.

It’s not often that a sports story reaches the top reaches of the news agenda without a spectacular win, crushing defeat or David-versus-Goliath scenario going on. But the story of John Terry’s (right)

It’s not often that a sports story reaches the top reaches of the news agenda without a spectacular win, crushing defeat or David-versus-Goliath scenario going on. But the story of John Terry’s (right)  Terry has been charged with racially abusing QPR’s Anton Ferdinand. He denies the charges, and the court case has been adjourned – therefore he has been found guilty of nothing. The FA decision – in which England manager Fabio Capello (left) was not invited to be involved – stated that it was made without inferring “any suggestion of guilt in relation to the charge” Terry faces.

Terry has been charged with racially abusing QPR’s Anton Ferdinand. He denies the charges, and the court case has been adjourned – therefore he has been found guilty of nothing. The FA decision – in which England manager Fabio Capello (left) was not invited to be involved – stated that it was made without inferring “any suggestion of guilt in relation to the charge” Terry faces. The Telegraph’s Sue Cameron has highlighted a row about

The Telegraph’s Sue Cameron has highlighted a row about